Why become a fat adapted runner?

Short answer:

- By using fat we get access to a huge store of energy (even in the thinnest person)

- Each molecule of fat gives us between 4 and 10 times the amount of energy that is available from a molecule of glucose

There has been quite a lot of discussion in endurance running publications about keto diets, low carb training, fat adaptation and so on. Some people claim that endurance runners thrive once they become fat adapted, whilst others claim that performance tanks if these runners don’t eat sufficient quantities of carbs, especially prior to competition. Studies have been performed on endurance athletes giving results that support each viewpoint! Many of the studies have significant limitations, but I won’t go any further into that in this post.

As a Lydiard coach, the concept of being metabolic flexible is something that I feel is important in enabling runners to improve performance. Part of metabolic flexibility is having reliable easy access to the fat stores in our bodies in addition to being able to access our glycogen stores at specific points in our training and especially when racing. I am not directing this blog post to elite athletes (who already have many well-qualified advisors on their teams) but rather towards those of us who are recreational runners with an eye on achieving some personal performance goal.

Metabolic flexibility is an ability to access our fat stores as well as our glycogen stores. This is important because even the leanest individuals have about 50,000 calories stored as fat in their bodies. Depending on pace, terrain, wind resistance, bodyweight etc., running for 30 minutes uses between 300 and 600 calories. So, using up 50,000 calories would take quite a long time! In contrast, we can only store about 1500 to 2000 calories as glycogen, a stored form of glucose that represents a readily available source of energy in the body. So we may run out of that energy relatively quickly.

The other major issue is that fat yields way more ATP (adenosine tri phosphate – the molecules that we use to provide our bodies with energy) than glucose. Without going into biochemistry – when we are running aerobically (i.e at easy to moderate effort levels):

- a molecule of fat can provide between 129 and 402 ATP molcules

- a molecule of glucose gives us only 36 ATP.

If we go into the anaerobic zone (by running with high effort levels that we can’t sustain for more than a 4-8 minutes) we can only use glucose and we have to use it less efficiently … getting just 2 ATP molecules in return! That sounds like a lot of effort and relatively little reward to me!!

We are probably well advised to stay out of that anaerobic effort zone, where we run ‘gaspy’ rather than ‘chatty’, apart from during short specific blocks of training in the final couple of months before our target race. Most of the time, in training, we should be aiming to develop our metabolic flexiblity.

So, how do we get ‘fat adapted’ or, as I prefer to say, ‘metabolically flexible’?

Short answer:

- by training aerobically – so we are preferentially using fat as our energy source and

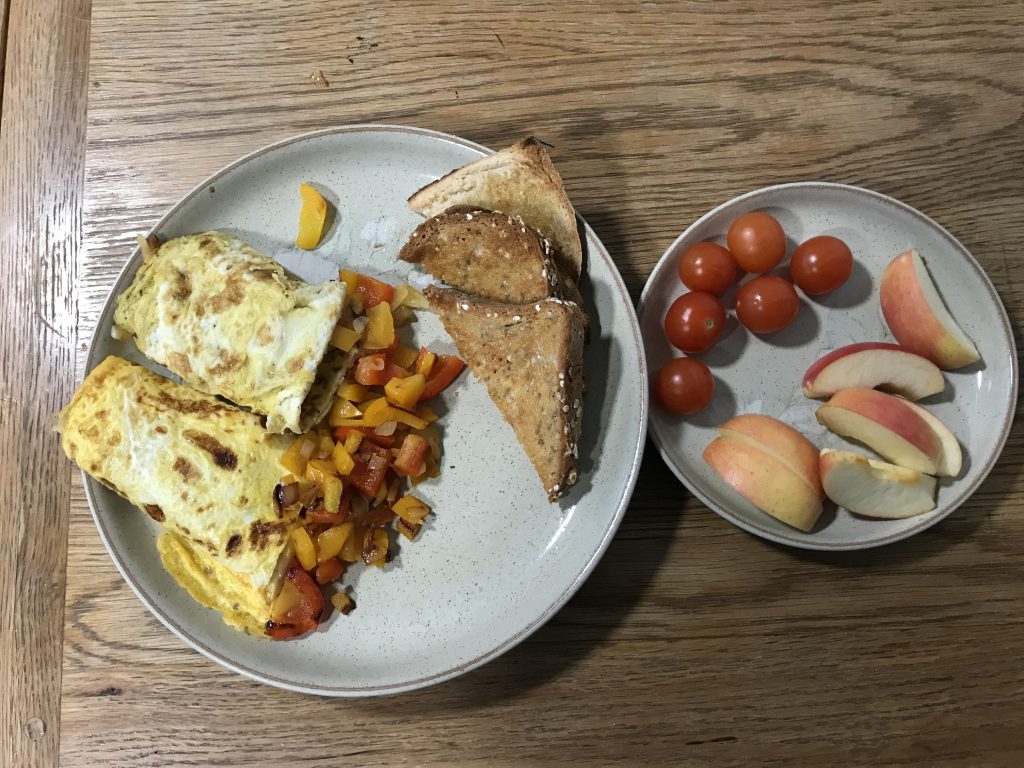

- by eating a healthy well-balanced diet that has lowish levels of low GI carbs and good amounts of high quality protein and healthy fats

I wasn’t an endurance athlete as a youngster but I believe that the way we lived and ate helped me to become metabolically flexible. This is an anecdote so I can’t prove this system works in general or even in particular (as no-one thought us important enough to study!). However, this story has a lot in common with current thinking on metabolic flexibility!

I grew up on a dairy farm. We got up about 5 am, had a drink of water, and went out to work on the farm. We worked steadily at a moderate level of effort – milking cows, feeding calves etc – for about 4 hours before having breakfast (fasted aerobic training!). As we lived far from any shops, the diet was relatively plain and almost everything was cooked from ‘scratch’. So we had a lot of home-produced protein and home-grown fruit and vegetables, and our intake of ‘obvious’ carbohydrate was limited to potatoe and mainly homemade bread or porridge. Meals were regular – 3 per day with a quick cup of tea and a slice of bread as an after school snack. There were no energy gels or drinks, and no nibbles in between meals. Meals were fairly substantial – we ate enough to feel full as the next meal might be many hours away. Confectionary was a Sunday treat and ‘bought cakes’ were for birthdays. I think it’s likely that this dietary regime, in combination with work that could be described as being aerobic or strength endurance in nature, contributed to our becoming metabolically flexible.

So my early childhood set me up to be a fat-adapted, or metabolically flexible, person. Despite some time spent not eating particularly well and not training much in the intervening years, I have been able to re-access that metabolic flexibility pretty much by doing the same things I did as a child – essentially:

- doing mostly aerobic training at effort levels that prioritise the use of body fat over glycogen,

- doing quite a bit of strength work to preserve muscle, and

- eating to satiety at every meal from a range of foods

- having a diet that contains good amounts of high quality protein and healthy fats and sufficient amounts of low Glycaemic Index (GI) carbs to cover my training needs.